My Philosophy: Land is Life

Only when we connect to nature, engage with nature, are we truly alive and vigorous. To really be alive, one must be under the sun, the moon, the shining stars and surrounded by the beautiful greenery and pure waters of the natural world

DAISAKU IKEDA

Nature, and connecting to the land, is one of the most important things in life. It allows us to know, do, and understand things that are just not possible from behind a desk, screen, or closed door.

I was fortunate to be born and raised on the extraordinary, traditional, ancestral, and unceded land of the Lhtako Dene First Peoples—in beautiful Quesnel, British Columbia. I continue to call this land home and am privileged to be raising my family here, enjoying all the opportunities it provides—from swimming, paddling, and skating its lakes to exploring its streams, rivers, and waterfalls; to biking, hiking, walking, and running its valleys and rolling hills to skiing and climbing its majestic mountains. This land blesses us with all four seasons: Springs amidst showers and flowers; Summers amidst sun and fun; Autumns amidst falling leaves and a chilly breeze; and Winters amidst the glow of snow.

My Pedagogy: Fostering Students’ Connection to People, Place & Land

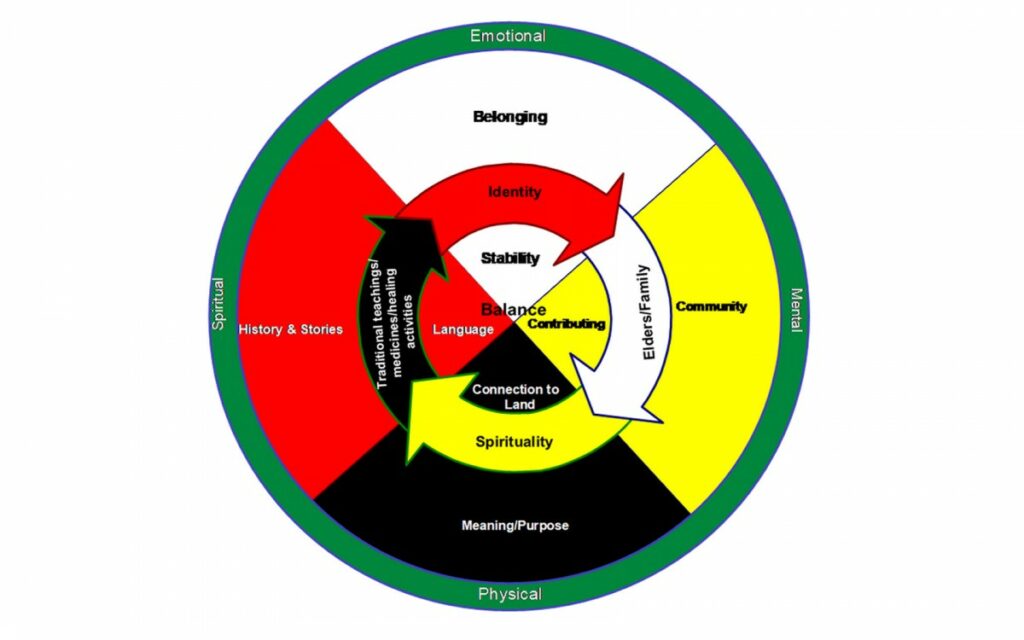

My aspects of self are fulfilled through mutually respectful and reciprocal relationships with family, friends, and community, and through my connection to the land—the mountains, forests, lakes, and rivers. When I fail to take care of myself, everything suffers—my mental and physical health, my relationships, my family, my students, and even my own learning. Meaningful learning is only possible when the whole self is considered and cared for—that is, an individual’s emotional, spiritual, physical, and mental needs must be met and balanced for them to learn, grow, and succeed.

If I, as the teacher, cannot engage in meaningful learning without first tending to these aspects of self, I cannot expect my students to learn without first tending to their whole selves—their need for belonging, identity, and stability; their need to connect and make contributions to community, elders, and family; their need for meaning, purpose, spirituality, and relation to the land; and their need to connect to their own histories, stories, traditional teachings, and language. As such, it is my personal mission to nurture students’ whole selves, drawing upon Indigenous epistemologies to foster understanding and find ways (individually and communally) to connect to people, place, and land. Then, and only then, can students reach their full potential within the walls of my classroom.

My Practice: Experiential, Place-Based Learning

I plan to employ my pedagogy throughout my entire practice—inside and outside the classroom. I want to help my students better understand and appreciate the land on which we are so fortunate to live—the stolen, ancestral, unceded territory of the Lhtako Dene First Peoples:

For those who want to live in deeply sacred and intimate relationship to the Land must understand that it first and foremost requires a respectful and consistent acknowledgement of whose traditional lands we are on, a commitment to journey—a seeking out and coming to an understanding of the stories and knowledge embedded in those lands, a conscious choosing to live in intimate, sacred, and storied relationship with those lands and not the least of which is an acknowledgement of the ways one is implicated in the networks and relations of power that comprise the tangled colonial history of the lands one is upon.

STYRES’ 2019, QTD. IN DOWNEY ET. AL., 2019, PG. 29

What better way to do this than outside—on the land—where students can fully immerse themselves in place. And what better guiding principles to rely on than those outlined in the First Peoples Principles of Learning (FNESC); in the 9 R’s (Respect, Relationships, Responsibilities, Reciprocity, Relevance, Reverence, Reclamation, Reconciliation, and Reflexivity) set out by Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991) and Fraser (2021); and in the 94 Calls to Action put forth by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015).

I want my students to understand that the land is a gift, given to us by the Ancestors, and that it has belonged to Indigenous peoples since time immemorial. In the words of the Elders: “we are the land, and the land is us.” I want my students to understand and appreciate Indigenous ways of knowing and being, to see how well these ways of knowing and being served Indigenous peoples in the past, and how well they can serve us (indigenous and non-indigenous) in the present and into the future—to help us live more sustainably and harmoniously together:

Rooted in and informed by understandings of the Land and self in-relationship that opens opportunities for decolonizing frameworks and praxis that critically trouble and disrupt colonial myths and stereotypical representations embedded in normalizing hegemonic discourses and relations of power and privilege.

STYRES’ 2019, QTD. IN DOWNEY ET. AL., 2019, PG. 24-25

I have been honing this approach with my own children for the past twelve years, and have had opportunities to use such an approach in a rural Northern BC classroom where myself, my co-teacher, the Indigenous Support Teacher, and two amazing Indigenous Elders worked together to ensure that our classroom (indoor and outdoor) was a place of equitable learning, one where Indigenous learners, alongside their non-Indigenous peers, felt safe and confident in their ways of knowing and being. Students participated in Dakelh language lessons delivered by an Indigenous Elder from the community. Various Elders gifted us their time, voice, and knowledge, coming to our classroom to share traditions and pass along cherished stories and legends centered on the importance of people, place, and land; on connections to ancestors, family, community, languages, and the traditional territories that sustained them.

Students had the opportunity to see and touch important Indigenous artifacts, to taste and smell traditional foods, and hear traditional music and voices. Students participated in Smudging Ceremonies, made talking sticks, and took part in story circles where they shared personal experiences. “Friday Forest, Fort, and Forage Days” and “Winter and Summer Solstice Days” were implemented to give students time to immerse themselves in nature, on the land, and explore how their in-class Indigenous learning and the First People Principles could be applied outside the classroom. As a class, and in small groups, students worked together to create shelters, make fire, and build traditional tools and weapons; identified plants, berries, and animal prints; fished with fishing rods they carved; and made and cooked bannock over fire with berries they picked and boiled into a sweet jam.

My co-teacher and I provided time and made these opportunities a priority in our curriculum. We recognized that being on the land was critical to student learning (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) and reached out to our District’s Aboriginal Education Department who connected us to amazing Elders in our community. Aside our students, we collectively co-constructed, engaged, and participated in experiential, place-based learning. Both teachers and students gained so much, which is why I plan to continue using this approach in my future practice as a fully certified, classroom teacher! I look forward to many more years of meaningful outdoor, experiential, place-based learning; to fostering students’ connection to people, place, and land; and to sharing my passion for learning, for life, and for land!

Together in Education,

Ms. H ♥️

Snachalhuya

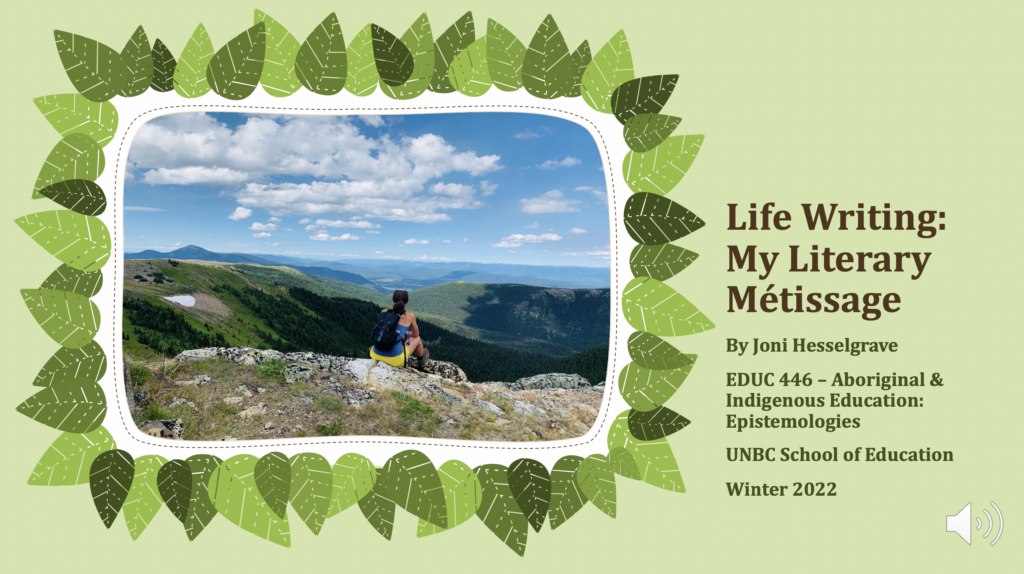

For a visual and narrated presentation of my philosophy, pedagogy, and practice, simply click this link to download. Once downloaded, click “Slideshow” – “Play Slideshow” to watch and listen to my commentary.

Hope you enjoy!

References:

Downey, Adrian M, Bell R., Copage K., Whittey P. (2019). Place-Based Readings Toward Disrupting Colonized Literacies: A Metissage. In Education, 25(2), 39-58.

First Nations Education Steering Committee (FNESC). (2008/2014). First Peoples Principles of Learning [poster]. Retrieved from http://www.fnesc.ca/first-peoples-principles-of-learning/

Fraser, Tina (2021). Nine R’s. University of Northern British Columbia.

Kirkness, V. and Barnhardt, R. (1991). First Nations and Higher Education: The Four R’s—Respect, Relevance, Reciprocity, Responsibility. The Journal of American Indian Education, 30(3), 1-15.

Mayes, Alison. (2019, January 30). Look to the medicine wheel for mental health, Elders advise in First Nationsstudy. Retrieved from https://news.umanitoba.ca/look-to-the-medicine-wheel-for-mental-health-elders-advise-in-first-nations-study/

Styres, S. (2019). Literacies of Land: Decolonizing Narratives, Storying, and Literature. In L.T. Smith, E. Tuck, & K. W. Yang (Eds.), Indigenizing and Decolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View (pg. 24-37). New York, NY: Routledge.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada., United Nations., National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation: Calls to Action.

The First Peoples Principles of Learning

The Nine R’s

Nine interwoven perspectives, or R’s, connected to the First Peoples Principles of Learning (FPPL) and the Professional Standards of BC Educators. Their purpose is to represent the significance of learning, looking, listening, and language. These perspectives derive from the scholarly works of Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991) which included the first four “R’s”, as well as the additional five “R’s” added by Fraser (2021):

- Respect – open to equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI), shared space, voice and vision, old and new knowledge, and more importantly, cultural safety amongst peers/colleagues, and visitors. We recognize that there are differences within cultures.

- Relationships – the ability to build capacity, share information that is beneficial to the needs of all learners.

- Responsibilities – students are responsible for their own learning and teaching. It is your responsibility to take what you have learned and to role-model, mentor, and to provide positive leadership to all learners.

- Reciprocity – the exchanging and dissemination of knowledge(s) as a gift. In my classes, “There is no right or wrong, only different”. Teaching and learning are reciprocal.

- Relevance – For protocols to be successful when entering the schools, visitors must have some understanding of the historical events that took place in that location, loss of identity, loss of language, disconnection from place and space, traditional and cultural practices, cultural laws, and structures. As researchers or visitors, we should be culturally aware of the “do and do not” and not assume that all communities have the same protocols or that the protocols are used for the same events or practices.

- Reverence – Indigenous people will share stories that personify lessons to be taught and learned. Their creation stories are usually connected to the animal world; mother earth, and everything that encompasses nature, the environment, eco-systems that allow Indigenous people to survive rather than destroy all things that is animate and imbued with spirit. As cultural beings, we require water to stay afloat, feel the energy and synergy provided by the creator. It is well noted by the Elders that, “we are the land, and the land is us.”

- Reclamation – As Indigenous people strive to reclaim their ways of knowing and being, there is a strong movement to reclaiming the essence of cultural practices, language revitalization, traditions, stories, songs, incantations, customs and protocols, treaties/land claims, preservation, and sustainability. Reclamation begins with the individual in search of their identity and including family, community, and nation. To reclaim traditional ways of knowing and being, it takes the collective.

- Reconciliation – According to the Truth and Reconciliation (2015), reconciliation is a process of healing of relationships that require public truth sharing, apology, and commemoration that acknowledge and redress past harms (p. 4). It also requires constructive action on addressing the ongoing legacies of colonialism that have had destructive impact on Indigenous peoples’ education, cultures and languages, health, child welfare, the administration of justice, and economic opportunities and prosperity (p.4). What will it take to acknowledge the past injustices in contemporary times? We all share responsibilities therefore, reconciling accountability, trust, collectivity, leadership, and respectful relationships are all necessary.

- Reflexivity – We all have different beliefs and practices, but what is important to note is how we view our journey, the influences that helps people to become enlightened, and most importantly, what we do with the knowledge. Reflexivity allows us the ability and awareness of how our beliefs, values, experiences, and practices become positive.

Lived Experience of the First Peoples Principles of Learning and the 9 R’s in My Practicums

As a practicum student, I encourage students to be patient and kind to themselves and others as they learn new concepts. All of the lessons and units I plan are delivered via open, non-judgmental group discussions, posited on positive teacher/student and student/student relationships and connections. Ideas and concepts are taught and learned experientially, through a mixture of explicit instruction, modelling, scaffolded support, practice, and student-doing. Student understanding is dependent upon their participation in, and attentiveness to, class and group discussions and to assigned tasks (done in class, with support as needed). Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is utilized to account for student diversity, allowing me to meet a broad range of student needs.

In my experiential practicum, I was also able to join my students on two fun-filled field trips to the local ski hill, where we enjoyed nature and connecting to the land with their families (siblings, parents, and even some grandparents/elders) on the traditional unceded territory of the Dakelh people.

Located on the traditional, unceded territory of the Dakelh people

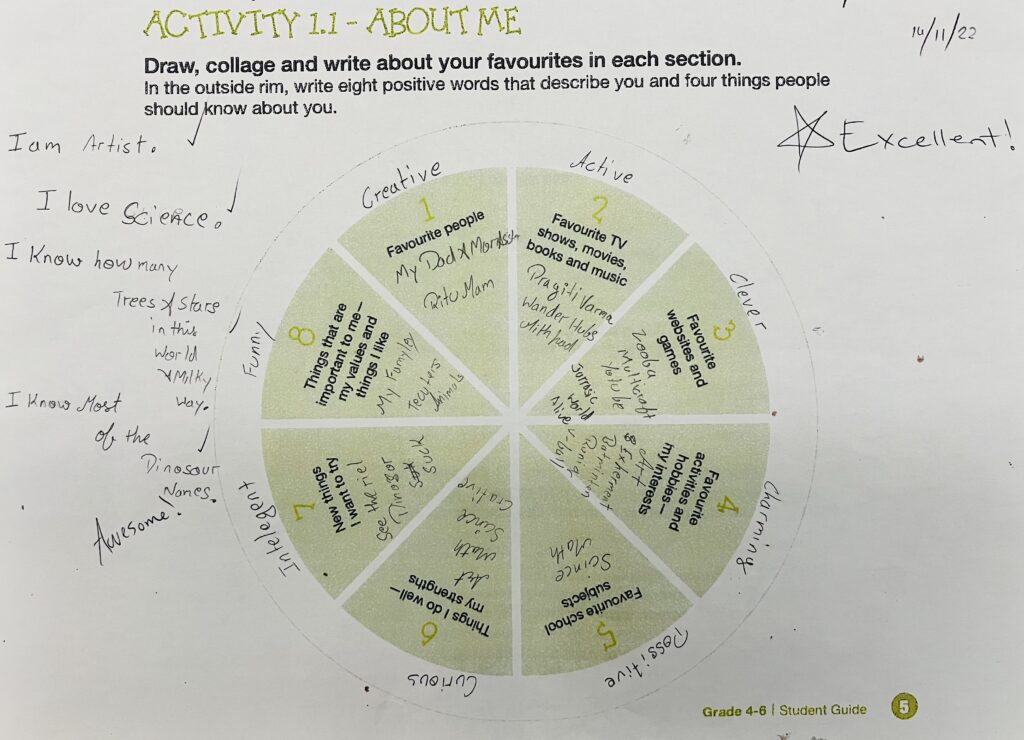

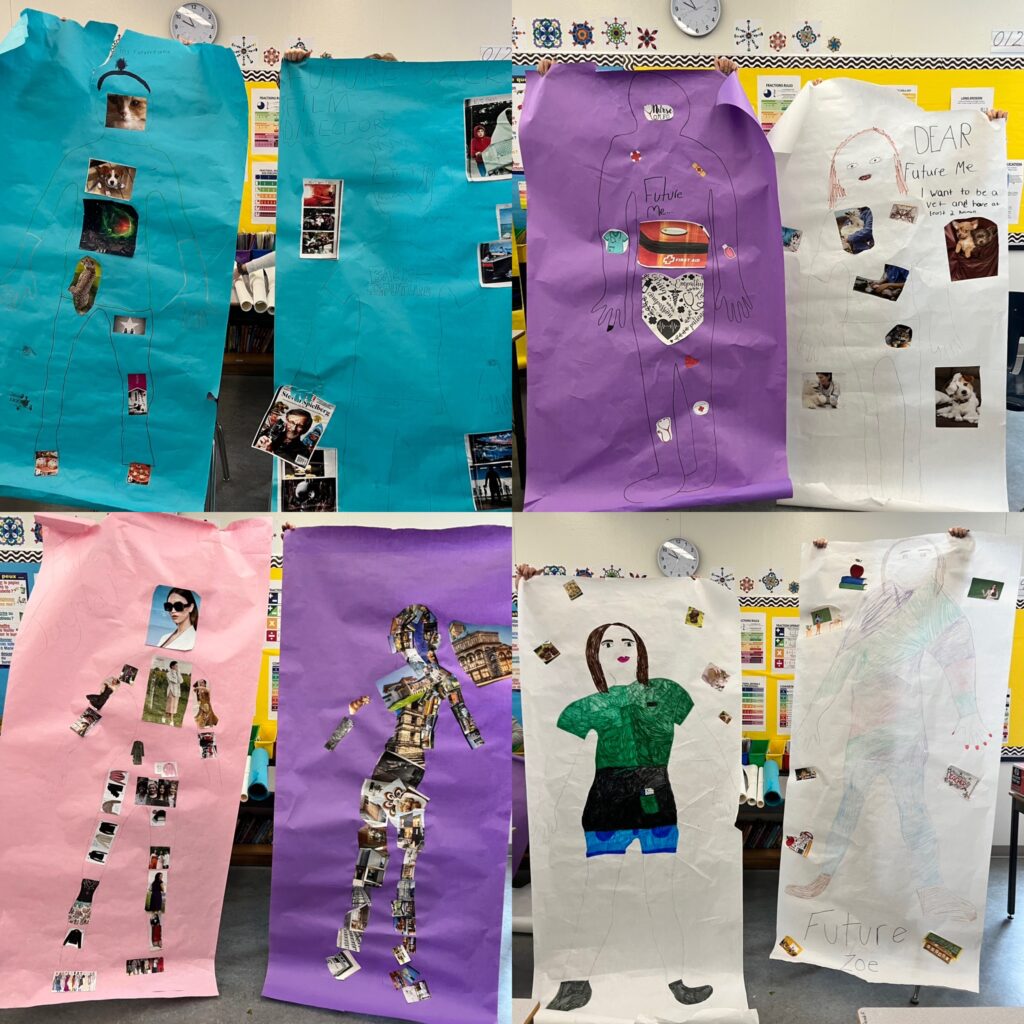

In my formative practicum, my coaching teacher and I worked together to ensure that our classroom was a place of equitable learning, one where everyone felt safe and confident in their ways of knowing and being. I planned lessons that would help me to gain meaningful insight into my students’ lives, so that I could really get to know them—their values, beliefs, likes, dislikes, interests, hobbies, strengths, and stretches. Students completed “About Me” wheels and had opportunities to share them with me and the class (if they were comfortable doing so). Students then used what they had discovered about themselves in their wheels to start exploring their future selves. This unit, which I titled “Present Me to Future Me” allowed students to focus on self, family, and their place in the community—now and into the future.

My coaching teacher and I also provided time and made outdoor opportunities a priority. We recognized that being on the land was critical to student learning. In my science unit, I made a concerted effort to bring in Indigenous perspectives. I got students outside (on the land) to explore space and our relationship within the universe and our Solar System. As a class, we discussed First Peoples’ perspectives of space and how Indigenous peoples have long looked to the sky for guidance and to help them predict and plan for change (in seasons, length of day, etc.).

Aside our students, my coaching teacher and I collectively co-constructed, engaged, and participated in experiential, place-based learning, wherein we explored the local “Wilde Trail”, observed different local trees, how they changed with the seasons, and how they could be identified by their bark, cones, and needles (or lack of).

Students also had the opportunity to build bird feeders for the local birds and squirrels, using cones I picked from the tress in my yard.

And, they participated in two Dakelh language and culture lessons, which were delivered by an Indigenous educator from our district, Ms. Arlene Horutko. Initially, my coaching teacher discussed cancelling these lessons (so as not to interfere with what I had planned for my practicum’s scope and sequence), but I was adamant that they continue as intended. I moved my lessons around and, alongside my students and coaching teacher, enjoyed learning about Indigenous knowledge, language, culture, and stories.

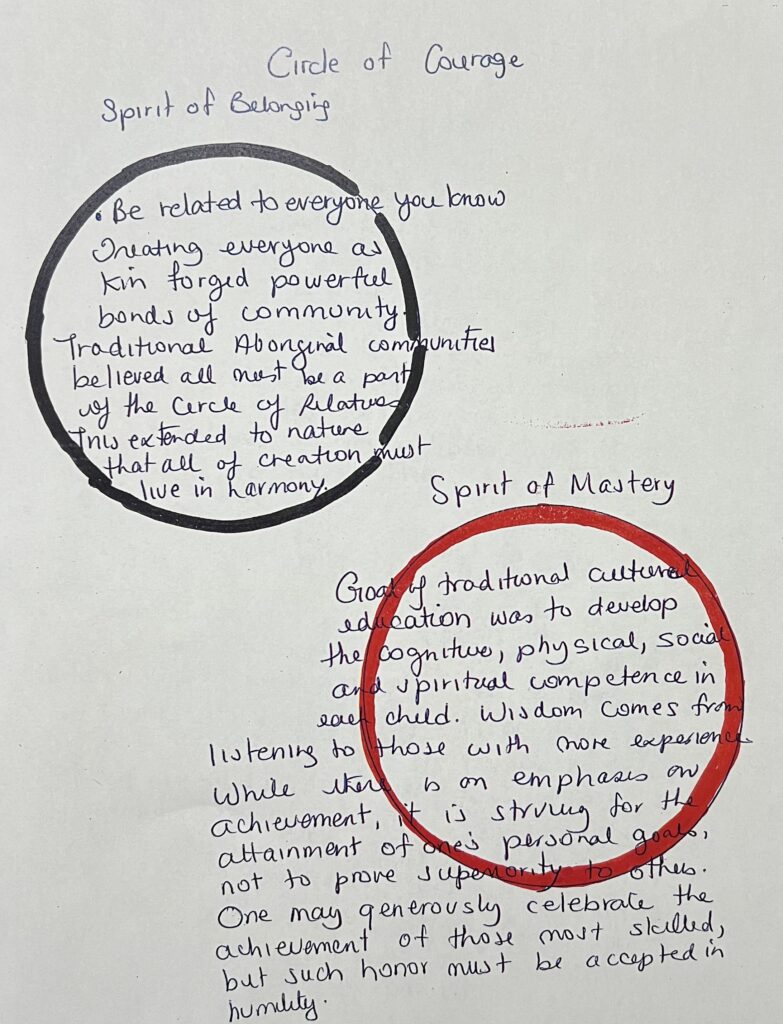

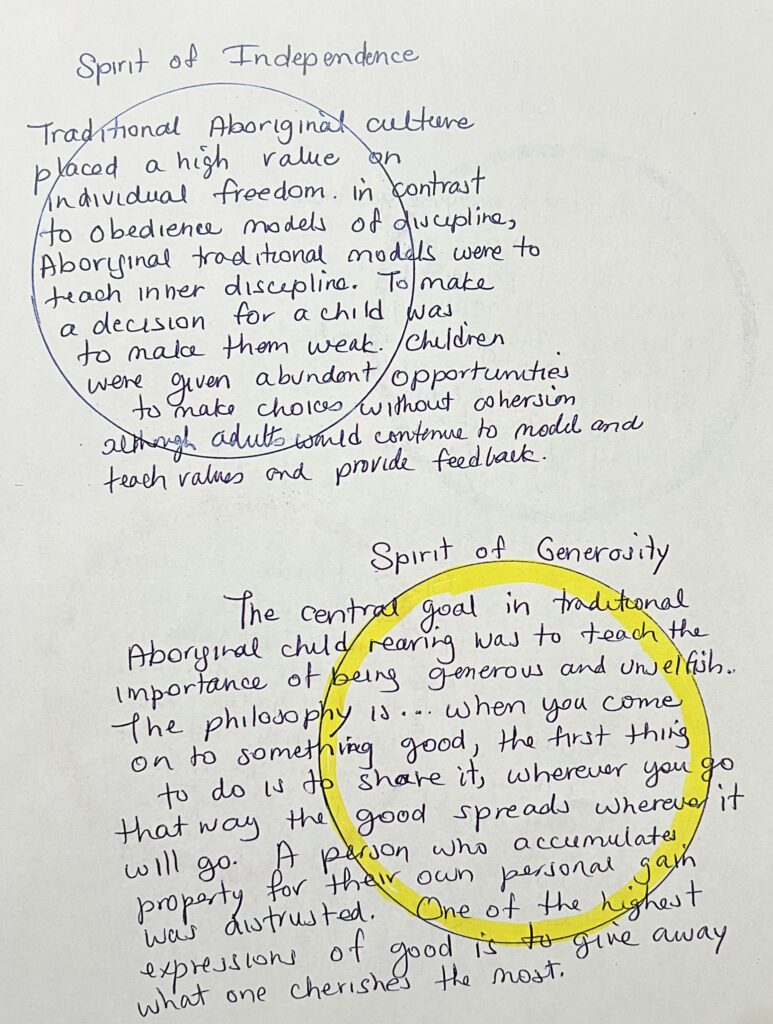

My coaching teacher and I also had the opportunity to attend our school district’s Indigenous Focus Day, wherein we joined together with all K-12 educators from our district to learn and grow in our collective understanding, knowledge, and application of Indigenous ways of knowing and being. It was a powerful day of communal learning that opened with a morning prayer from local elder, Ellie Peters, followed by Indigenous drumming and guest speaker, Kevin Lamoureux (Ensouling our Schools). Kevin spoke of the importance of Truth and Reconciliation and the 94 Calls to Action, specifically TRC 62.2: “providing teacher education on how to integrate and utilize Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods in classroom” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada). Kevin highlighted teachers and the important role they (we) play in moving society forward, toward a better future for ALL children. A future where schools are safer and happier places to learn (and teach). Kevin emphasized Dr. Martin Brokenleg’s Circle of Courage, its four quadrants of Belonging, Independence, Mastery, and Generosity, and how important they are to trauma-informed practice and “Mino-Pimatisiwin”—living in a good way. Kevin discussed how teachers must address all four quadrants, or core values, in order to create an environment where children can/will thrive.

Following Kevin’s speech, my coaching teacher and I joined the rest of our school in planning an Indigenous Culture Day, set to take place in the coming weeks. As a school, we discussed stations and activities ranging from Indigenous language games to Indigenous physical education games; from Indigenous stories and art to indigenous drumming and hoop dancing; as well as Bannock making. Then, in the afternoon, I had the pleasure of joining Doreen L’Hirondelle, District Principal of Aboriginal Education, as she continued the conversation and facilitated group dialogue regarding the importance of the Circle of Courage and how it can be brought into our classrooms going forward:

As a whole, my formative practicum was an enriching experience, one that honoured Standard 9, the First Peoples Principle of Learning, the 9 Rs, and Indigenous ways of knowing and being. I look forward to future Indigenous-focused learning in my summative practicum, and in my teaching career to come.

Together in Education,

Ms. H

Snachalhuya