I have, and always have had, two passions: learning and land. I value both passions dearly and it is my goal to pass them along to my students.

I want my students to value learning and be successful in school, and I know that valuing the land and connecting with nature facilitates this. Land and learning have a symbiotic relationship that helps individuals be successful in all aspects of life. As such, I present two very different (but equally important) personal educational philosophy statements:

Personal Educational Philosophy Statement #1

Educational philosophy provides a foundation which constructs and guides the ways knowing is generated and passed on to others. Therefore, it is of critical import that teachers begin to develop a clear understanding of philosophical traditions and how the philosophical underpinnings inform their educational philosophies; […] a clear educational philosophy will help guide and develop cohesive reasons for how each teacher designs classroom spaces and learning interactions with both teachers and students.

SUNY Oneonta Education Department

Educational philosophy, as an umbrella term, along with the many hard to pronounce philosophies (or “isms”) under the umbrella—Essentialism, Perennialism, Progressivism, and Critical Pedagogy—are new to my vocabulary, having only been added during my first semester as a teacher candidate in the Bachelor of Education Program at the University of Northern British Columbia. This does not mean, however, that I have not engaged with them. Over the past two and a half years, without even realizing it, I have spent a great deal of time shaping (and re-shaping) my personal educational philosophy while working as an uncertified teacher teaching on call (UTTOC). Although I had not expressed the exact words, I had—without question—actively negotiated them on a daily basis in the numerous and varied classrooms that I taught. This negotiation was not easy.

When I first entered K-12 classrooms, I was stunned to see how much they had changed since I attended. Gone were the students sitting neatly and quietly in rows, with their textbooks and notebooks opened, while their teachers instructed from the front of the room. Gone were the days of quiet and orderly work blocks, where teachers sat at their desks marking students’ assignments, quizzes, and tests while students worked diligently, getting up to move around only if they were approaching the teacher’s desk to ask a question or gain permission to use the washroom. Gone were the letter grades and assemblies where students received academic and athletic recognition.

These are the memories of my elementary school days. I flourished and excelled in those educational environments. As a student, I thrived on order, structure and a good challenge. I enjoyed working independently, was self-motivated, and had great time-management skills. I pushed myself to do the best I could. The thought of receiving anything less than an “A” was devastating. I was a “reading/writing” learner—understanding information by reading text and preferring to express my thoughts in written form. I loved my Houghton Mifflin textbooks; working through them, beginning to end, gave me great satisfaction. I was “that” student!!

So, to say that I was shocked by classrooms as a new teacher is an understatement. I was not at all prepared for the new era of classroom teaching. It felt as though I had been thrown into the deep end, without warning, with my hands tied behind my back. Classrooms were loud and often chaotic, with so much flexibility that it was hard (without classroom management training) to maintain a semblance of “control.” In addition, I was “just a sub” and students often acted out more with a substitute teacher than they did with their regular classroom teacher. Adding salt to the wound, it felt as though I had more eyes on me as an uncertified TTOC than there would have been if I was a certified TTOC. I constantly felt the need to prove my worth and show that I was capable of managing (not just teaching) a classroom of students. The label “uncertified” carries with it a heavy burden, one that depicts a teacher as unqualified and not fully capable of doing her job. In this environment, it was hard to discern a personal educational philosophy. I was in survival mode, trying my best to make it through the day unscathed!

As I gained experience, I gained confidence. I also cultivated a host of crucial skills in classroom management, allowing me to implement important rules, routines, and procedures in the classrooms I taught—even if it was only for the one day I was there. I realized the importance of teacher-student and student-student connection and relationship-building—again, even if it was only for the one day I was there. I refined my techniques and strategies for giving explicit, effective, engaging, and differentiated instruction. I became more skilled in lesson implementation and follow through. And, I came to the realization that I was not failing—that is, all classrooms, not just the ones I was standing in, were loud and often chaotic; that it was not a reflection of my incapability, but rather a change in how students engage and participate in their learning. If my students were not sitting quietly in their rows, that was okay (they were collaborating); if their textbooks and notebooks were not out, that was okay too (learning does not just happen via textbooks); if I was not at the front instructing, or at my desk marking, that was also okay (those are not the only places teaching occurs). Other teachers were not judging me from across the hall because their classrooms looked and sounded just like mine!

When I came to these realizations, it clicked: my classrooms were not going to look or sound like they did when I was a young student and I was not going to teach like my teachers had taught. However, as Parker Palmer argues, “we teach who we are,” and there is a strong correlation between my life experience and my educational philosophy that cannot be separated. My life, not only in school, but also at home, was based on structure, guidance, ethics, expectations, dedication, and opportunity, as well as the 5 C’s: commitment, care, courage, consciousness, and centeredness (Litz, 2021). Growing up, I had extremely supportive parents who instilled me with the successful learner traits of compassion, creativity, enthusiasm, confidence, risk-taking, strategy, industriousness, and thoughtfulness (Successful Learners); my home was safe, secure, and nurturing; I had a community of friends, family, and coaches; and my educators were leaders in their profession. As such, my personal educational philosophy holds tight to these aforementioned values and I will bring them into every classroom, and to every student, I teach.

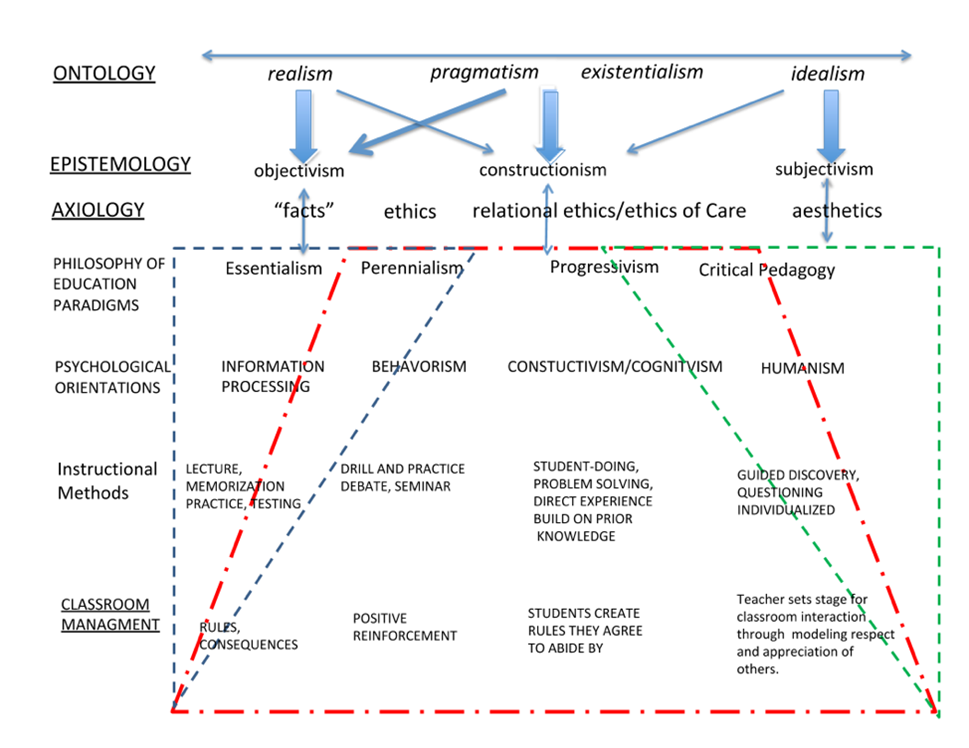

Had you asked me what my educational philosophy was ten weeks ago, I would have told you that it was ‘a little old school.’ But I have been enlightened by my professors and the scholarly knowledge they provided—to a point where I can elaborate on my ‘old school’ ways. Drawing on Table 1: Philosophies of Education Matrix (below), I am now able to translate my educational philosophy to the academic vocabulary of our profession.

I believe that “student doing, problem solving, direct experience, build on prior knowledge” is the most effective means of instruction because only by doing can a student better understand concepts and content; only through problem solving and direct experience can students gain familiarity with subject matter/material and understand their own ways of learning; and only prior knowledge can serve as the base upon which students build on their learning.

I think “positive reinforcement” is the optimum classroom management technique because students are more likely to respond positively when given positive feedback; it is a necessary component of engagement and facilitates positive relationships between teachers and student and between student and school expectations/rules/boundaries. In Every Kid Needs a Champion (2013), Rita Pierson argues that “kids don’t learn from people they don’t like”; that learning only occurs when there is a positive relationship between student and teacher; that relationships must be built upon positive, not negative, reinforcement—that is: “say they are good or successful enough times and they’ll believe it!”

My choices with regard to instruction and classroom management align within the central area of Table 1, between the ontologies of Pragmatism and Existentialism; beneath the epistemology of Constructionism; and under the axiology of Relational Ethics/Ethics of Care. My philosophy of education, therefore, is one of Progressivism with a psychological orientation of Constructivism/Cognitivism. This definitely sounds more professional than ‘a bit old school.’

My educational philosophy guides me each time I enter a new classroom as an UTTOC; it will continue to guide me as a teacher candidate in her practicums over the course of this program; and, it will lead me into future classrooms, schools, and school communities as a certified teacher. What we, as teachers, do in educational institutions is important and within our control. I will never be able to control the educational system, or the shifting educational paradigm, but I can control how I function in them. I vow to continuously build and develop my personal educational philosophy so that I can function in educational settings to the best of my ability!

Together in education,

Ms. H ♥️

References

Litz, David. (2021, September 16). Qualities of Good Teachers: 5 C’s in Education: The Heart of a Teacher and Metaphors. [PowerPoint]. Retrieved from https://learn.unbc.ca/bbcswebdav/pid-241421-dt-content-rid-2071036_1/xid-2071036_1

Palmer, P.J. (1997). The Heart of a Teacher: Identity and Integrity in Teaching. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 29(6), 14-21.

Pierson, Rita. (2013, May 3). TED Talks Education. Every Kid Needs a Champion. [Video] You Tube – TED. Uploaded on September 20, 2021 from https://www.ted.com/talks/rita_pierson_every_kid_needs_a_champion

Successful Learners. (2015-2021). Traits. Accessed on October 9, 2021 from

SUNY Oneonta Education Department. (n.d.). Foundations of Education: 5.1 Foundations of Education Philosophy. Attribution Foundations of Education. Uploaded on September 13, 2021 from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-oneonta-education106/chapter/5-1-foundations-of-educational-philosophy/

Values and Goals Continued

Personal Educational Philosophy Statement #2

Only when we connect to nature, engage with nature, are we truly alive and vigorous. To really be alive, one must be under the sun, the moon, the shining stars and surrounded by the beautiful greenery and pure waters of the natural world

Daisaku ikeda

My Philosophy: Land is Life

Nature, and connecting to the land, has always been one of the most important things in my life. It makes me feel alive and has made me who I am today—a strong, adventurous, daring, determined, positive, and grateful woman, mother, daughter, sister, friend, student, and teacher. Land is what I seek, and nature where I go, when I am frustrated, sad, or anxious—when I need to escape the stress and worries of the world; where I decompress, clear my head, and find solutions to life’s problems. Land is also what I seek, and nature where I go, when I am happy, excited, or energized; where I celebrate my successes, connect with family and friends, and challenge myself to do things that are not possible from behind a desk, screen, or closed door.

I was fortunate to be born and raised on the extraordinary, traditional, ancestral, and unceded land of the Lhtako Dene First Peoples—in beautiful Quesnel, British Columbia. I continue to call this land home and am privileged to be raising my family here, enjoying all the opportunities it provides—from swimming, paddling, and skating its lakes to exploring its streams, rivers, and waterfalls; to biking, hiking, walking, and running its valleys and rolling hills to skiing and climbing its majestic mountains. This land blesses us with all four seasons: Springs amidst showers and flowers; Summers amidst sun and fun; Autumns amidst falling leaves and a chilly breeze; and Winters amidst the glow of snow.

No matter the day or the feeling, I yearn to be walking or running the trails of our deep forests, fully engulfed by lush trees and the sounds of birds chirping. I crave our crisp, clean, mountain air and scenic valley views, which only climbing beyond the tree line provides. I thirst for the crushing waters of our plunging waterfalls and riverbeds. I ache for our lakes and freshwater lapping against a nearby shore. No matter where I am, or what I am doing, I long for the sun to kiss my skin, the wind to rustle my hair, and the sand, soil, or surf to grace my feet.

The land grounds me, it is my steadfast and dependable outlet:

No matter the circumstance, the land is there: dependable, reliable, and always available. Friends, family, and acquaintances get busy, but the land is never too busy; it is continuously there to help me find ME—to ground me and remind me who I am and what is important (and not important). Whenever I am not feeling myself, I know that I need to drop what I am doing and head outdoors! Sometimes this is hard, especially as of late when work and school occupy so much of my time, but I know that it is a need I cannot ignore. It is in these busy times that I need the land the most. The time I spend in nature, connecting to the land, is time spent connecting to myself and to life. When I neglect this connection, I lose myself—I become ungrounded.

The land saves me, it is my rescue and my refuge and has aided me in my most trying times:

There were times in my past where I failed to foster this connection and lost sight of who I was. A toxic person in my life actively worked to disconnect me from the land; he did not share my passion for, or connection to, the land. Eventually, this person began to envy the time I spent away from him and made me feel guilty for pursuing my passions. Under the weight of this guilt, I began to explore and adventure less and less. In turn, I began to feel less and less like myself—I was losing who I was. It took a tragic accident for me to realize that I could no longer let this happen—I had to find myself again! I cut ties with the individual and have spent the past six years rekindling my connection to the land: seeking rescue and refuge in the forests, mountains, lakes, and rivers of my hometown; completing various summit challenges, chasing waterfalls, riverbed hopping, paddling lakes, and biking and hiking wherever my legs will take me. My connection to the land has never been stronger and I feel more like myself than I ever have!

The land frees me, it is my motivator to be the best version of myself:

It is so very freeing to feel like me again—not just for me, but for my children, my family, my friends, and my community. I am a better person—the best version of myself—which means I can be the best parent to my three incredible children; the best daughter to my amazing and supportive parents; the best friend to my wonderful and caring comrades; the best teacher to the hundreds of children I teach each week; and the best student to accomplish my goal of becoming a fully certified teacher. I finally feel like I can do anything I set my mind to—all thanks to making and taking time to connect to the land (solo and with my children, parents, and like-minded friends).

My Pedagogy: Fostering Students’ Connection to People, Place & Land

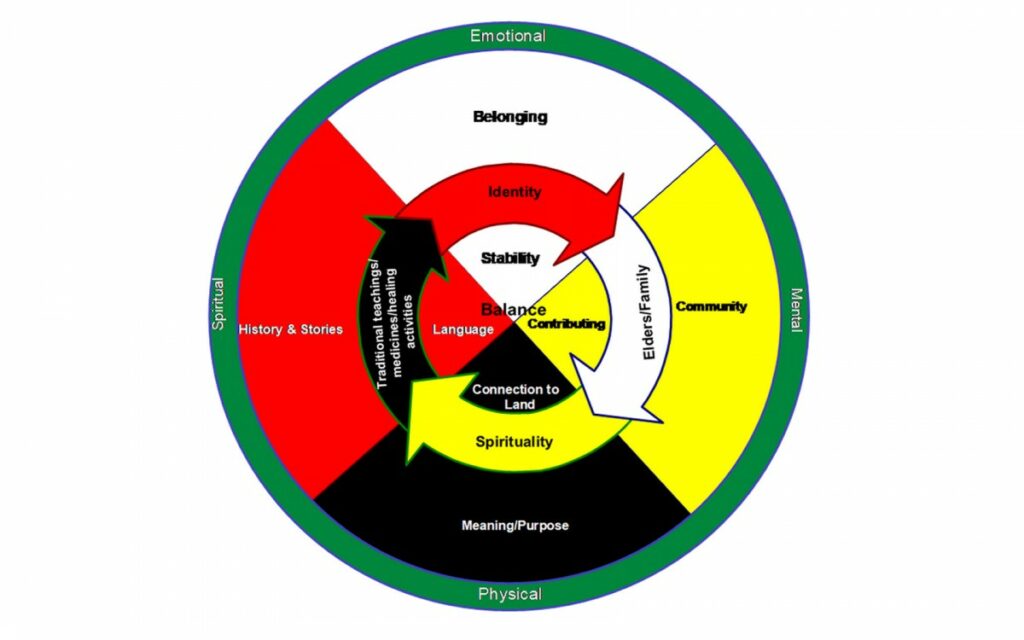

Clearly, my aspects of self are fulfilled through mutually respectful and reciprocal relationships with family, friends, and community, and through my connection to the land—the mountains, forests, lakes, and rivers. When I fail to take care of myself, everything suffers—my mental and physical health, my relationships, my family, my students, and even my own learning. Meaningful learning is only possible when the whole self is considered and cared for—that is, an individual’s emotional, spiritual, physical, and mental needs must be met and balanced for them to learn, grow, and succeed.

If I, as the teacher, cannot engage in meaningful learning without first tending to these aspects of self, I cannot expect my students to learn without first tending to their whole selves—their need for belonging, identity, and stability; their need to connect and make contributions to community, elders, and family; their need for meaning, purpose, spirituality, and relation to the land; and their need to connect to their own histories, stories, traditional teachings, and language. As such, it is my personal mission to nurture students’ whole selves, drawing upon Indigenous epistemologies to foster understanding and find ways (individually and communally) to connect to people, place, and land. Then, and only then, can students reach their full potential within the walls of my classroom.

My Practice: Experiential, Place-Based Learning

I plan to employ my philosophy and my pedagogy throughout my entire practice—inside and outside the classroom. I want to help my students better understand and appreciate the land on which we are so fortunate to live—the stolen, ancestral, unceded territory of the Lhtako Dene First Peoples:

For those who want to live in deeply sacred and intimate relationship to the Land must understand that it first and foremost requires a respectful and consistent acknowledgement of whose traditional lands we are on, a commitment to journey—a seeking out and coming to an understanding of the stories and knowledge embedded in those lands, a conscious choosing to live in intimate, sacred, and storied relationship with those lands and not the least of which is an acknowledgement of the ways one is implicated in the networks and relations of power that comprise the tangled colonial history of the lands one is upon.

Styres’ 2019, qtd. in Downey et. al., 2019, pg. 29

What better way to do this than outside—on the land—where students can fully immerse themselves in place. And what better guiding principles to rely on than those outlined in the First Peoples Principles of Learning (FNESC); in the 9 R’s (Respect, Relationships, Responsibilities, Reciprocity, Relevance, Reverence, Reclamation, Reconciliation, and Reflexivity) set out by Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991) and Fraser (2021); and in the 94 Calls to Action put forth by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015).

I want my students to understand that the land is a gift, given to us by the Ancestors, and that it has belonged to Indigenous peoples since time immemorial. In the words of the Elders: “we are the land, and the land is us.” I want my students to understand and appreciate Indigenous ways of knowing and being, to see how well these ways of knowing and being served Indigenous peoples in the past, and how well they can serve us (indigenous and non-indigenous) in the present and into the future—to help us live more sustainably and harmoniously together:

Rooted in and informed by understandings of the Land and self in-relationship that opens opportunities for decolonizing frameworks and praxis that critically trouble and disrupt colonial myths and stereotypical representations embedded in normalizing hegemonic discourses and relations of power and privilege.

Styres’ 2019, qtd. in Downey et. al., 2019, pg. 24-25

I have been honing this approach with my own children for the past twelve years, and have had opportunities to use such an approach in a rural Northern BC classroom where myself, my co-teacher, the Indigenous Support Teacher, and two amazing Indigenous Elders worked together to ensure that our classroom (indoor and outdoor) was a place of equitable learning, one where Indigenous learners, alongside their non-Indigenous peers, felt safe and confident in their ways of knowing and being. Students participated in Dakelh language lessons delivered by an Indigenous Elder from the community. Various Elders gifted us their time, voice, and knowledge, coming to our classroom to share traditions and pass along cherished stories and legends centered on the importance of people, place, and land; on connections to ancestors, family, community, languages, and the traditional territories that sustained them.

Students had the opportunity to see and touch important Indigenous artifacts, to taste and smell traditional foods, and hear traditional music and voices. Students participated in Smudging Ceremonies, made talking sticks, and took part in story circles where they shared personal experiences. “Friday Forest, Fort, and Forage Days” and “Winter and Summer Solstice Days” were implemented to give students time to immerse themselves in nature, on the land, and explore how their in-class Indigenous learning and the First People Principles could be applied outside the classroom. As a class, and in small groups, students worked together to create shelters, make fire, and build traditional tools and weapons; identified plants, berries, and animal prints; fished with fishing rods they carved; and made and cooked bannock over fire with berries they picked and boiled into a sweet jam.

My co-teacher and I provided time and made these opportunities a priority in our curriculum. We recognized that being on the land was critical to student learning (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) and reached out to our District’s Aboriginal Education Department who connected us to amazing Elders in our community. Aside our students, we collectively co-constructed, engaged, and participated in experiential, place-based learning. Both teachers and students gained so much, which is why I plan to continue using this approach in my future practice as a fully certified, classroom teacher! I look forward to many more years of meaningful outdoor, experiential, place-based learning; to fostering students’ connection to people, place, and land; and to sharing my passion for learning, for life, and for land!

Together in Education,

Ms. H ♥️

Snachalhuya

For a visual and narrated presentation of this philosophy, simply click this link to download. Once downloaded, click “Slideshow” – “Play Slideshow” to watch and listen to my commentary. Hope you enjoy!

References

Downey, Adrian M, Bell R., Copage K., Whittey P. (2019). Place-Based Readings Toward Disrupting Colonized Literacies: A Metissage. In Education, 25(2), 39-58.

First Nations Education Steering Committee (FNESC). (2008/2014). First Peoples Principles of Learning [poster]. Retrieved from http://www.fnesc.ca/first-peoples-principles-of-learning/

Fraser, Tina (2021). Nine R’s. University of Northern British Columbia.

Kirkness, V. and Barnhardt, R. (1991). First Nations and Higher Education: The Four R’s—Respect, Relevance, Reciprocity, Responsibility. The Journal of American Indian Education, 30(3), 1-15.

Mayes, Alison. (2019, January 30). Look to the medicine wheel for mental health, Elders advise in First Nations study. Retrieved from https://news.umanitoba.ca/look-to-the-medicine-wheel-for-mental-health-elders-advise-in-first-nations-study/

Styres, S. (2019). Literacies of Land: Decolonizing Narratives, Storying, and Literature. In L.T. Smith, E. Tuck, & K. W. Yang (Eds.), Indigenizing and Decolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View (pg. 24-37). New York, NY: Routledge.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada., United Nations., National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation: Calls to Action.