Author: hesselgra Page 8 of 9

I am a first year teacher candidate in the Bachelor of Education program at the University of Northern British Columbia. I hold a Bachelor of Arts (Geography/History), also from UNBC, and am currently working as a non-certified teacher teaching on call (TTOC) in School District #28, Quesnel, BC.

I have three amazing, busy children whom I enjoy mountain biking, hiking, swimming, paddling, wakesurfing, and adventuring with in our community and surrounding area. We are so fortunate to be living a wonderful life on the traditional and unceded territory of the Lhtako Dene' peoples.

EDUC 446 Provocation Post #2

Provocation: Brainstorm the practical applications of the readings in a 21st century, Northern BC classroom. Consider how teachers (both settlers and Indigenous) can create a more equitable experience for Indigenous learners and teach with fidelity to the First Peoples Principles of Learning. What does the experience for learners look like, sound like, and feel like? Explore the role of the teacher in the classroom.

Dawn Zinga’s chapter, “Teaching as the Creation of Ethical Space”, from Indigenous Education (Huia et al, 2019), tasks instructors, faculty, and upper level administrators with a number of responsibilities: to become more aware of the challenges facing Indigenous students in post-secondary spaces; to recognize that such spaces are highly contested and why; to see and understand the ways in which we, as educators, are closely implicated in these contested spaces; to carve out “ethical space” within educational institutions and our practices; and, most importantly, to act and engage purposefully in these “ethical spaces.”

Zinga argues, and I agree, that it has been easy for non-Indigenous students, instructors, and administration to feign ignorance and perpetuate colonial power within educational institutions, drawing upon Foucault’s idea of settlers being “willing vehicles of power” (1977, 1998), and she calls on those in education to push back against the western, Eurocentric “status quo.” Zinga calls for the removal of the “pathologizing lens”, which frames challenges facing Indigenous students as “Indigenous problems” or a “crisis in Indigenous education”, and asks us to equip ourselves with a lens that sees the problem(s) for what they really are—products of colonialism, residential schools, and the Eurocentric belief that Western ways of being and knowing are superior to those of Indigenous ways of being and knowing.

Zinga’s concept of “ethical space” is extremely important and something I deeply connected to. As a Social Geography major, ‘space’ is something I have explored at length; it encompasses so much more than physical space—it has cultural, social, emotional, psychological, meta-physical, sexual, racial, ethnic, and gendered aspects; it is the space that occupies our minds, bodies, and souls; it resonates in our homes, communities, and the places we inhabit (i.e. the educational institutions Zinga discusses).

Zinga’s “ethical space”, combined with the First Peoples Principles of Learning (FNESC) and Dr. Tina Fraser’s 9 R’s (2021), based on the work of Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991), provides a powerful approach to teaching in 21st century, Northern BC classrooms—an approach I had the privilege of being a part of while teaching Grade 4/5 at Parkland Elementary School (one of Quesnel’s rural, land-based schools located near Ten Mile Lake). Myself, my co-teacher, the Indigenous Support Teacher, and two amazing Indigenous Elders worked together to ensure that our classroom was a place of equitable learning, one where Indigenous-learners, alongside their non-Indigenous peers, felt safe and confident in their ways of being and knowing.

Students participated in Dakelh language lessons delivered by an Indigenous Elder from the community. Various Elders gifted us their time, voice, and knowledge, coming to our classroom to share traditions and pass along cherished stories and legends centered on the importance of “people, place, and land”; on connections to ancestors, family, community, languages, and the traditional territories that sustained them. Students had the opportunity to see and touch important Indigenous artifacts, to taste and smell traditional foods, and hear traditional music and voices. Students participated in Smudging Ceremonies, made talking sticks, and took part in story circles where they shared personal experiences. “Friday Forest, Fort, and Forage Days” and “Winter and Summer Solstice Days” were implemented to give students time to immerse themselves in nature and explore how their in-class Indigenous learning and the First People Principles could be applied outside the classroom. As a class, and in small groups, students worked together to create shelters, make fire, and build traditional tools and weapons; identified plants, berries, and animal prints; fished with fishing rods they carved; and made and cooked bannock over fire with berries they picked and boiled into a sweet jam.

My co-teacher and I provided time and made these opportunities a priority in our curriculum. We recognized that “ethical space” was critical to student learning (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) and reached out to our District’s Aboriginal Education Department who connected us to amazing Elders in our community. Aside our students, we collectively co-constructed, engaged, and participated in “ethical space”—making the space and experience one of fulfillment and enrichment for all involved!

References

- Dr. Tina Fraser’s 9 R’s, based on the work of Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991) with the addition of her five R’s (2021), which together “represent the significance of learning, looking, listening, and language” in the classroom.

- The First Peoples Principles of Learning (FNESC n.d.) “Teaching as the Creation of an Ethical Space” (Zinga, 2019) from Indigenous Education (Huia et al, 2019)

EDUC 393 Cross-curricular Reflexive Writing #2

In my first cross-curricular reflexive writing assignment, I focused on educational paradigms and their ability to shift and keep pace in our changing world. I drew upon Sir Ken Robinson and his argument that it comes down to the “structures and habits of our institutions and the habitats they occupy” (2010). I spoke of the challenges facing teachers in these institutions and habitats; of how difficult it is for them to keep up with the rapidly changing structures and habits within them. What I did not address, as pointed out in your feedback, is how I see myself, and my emerging teaching philosophy, connecting to the foundational philosophies of our profession:

A philosophy grounds or guides practice in the study of existence and knowledge, while developing an ontology (the study of being) on what it means for something or someone to be—or exist. Educational philosophy, then, provides a foundation which constructs and guides the ways knowing is generated and passed on to others. Therefore, it is of critical import that teachers begin to develop a clear understanding of philosophical traditions and how the philosophical underpinnings inform their educational philosophies; because a clear educational philosophy will help guide and develop cohesive reasons for how each teacher designs classroom spaces and learning interactions with both teachers and students (SUNY Oneonta Education Department).

An important consideration that directly correlates to my effectiveness as a teacher within our professional institutions and habitats—in the classroom, school, and broader school community.

My first paper lacked personal agency. I got wrapped up with the systems and forgot that my personal agency is critical. What I do and who I am in educational institutions and habitats is important and within my control. I cannot control the systems, or the shifting educational paradigm, but I can control how I function in them. Thank you for the reminder and for challenging me to think about what it means to me, as a teacher candidate, with an emerging teaching philosophy. Parker Palmer (1997) asserts:

[I]f we want to develop the identity and integrity that good teaching requires, we must do something alien to academic culture: we must talk to each other about our inner lives, risky stuff in a profession that fears the personal and seeks safety in the technical, the distant, the abstract (p. 20).

Palmer’s push to embrace teaching from the heart has advanced our profession and led to improved teacher performance. Teachers in the profession are more comfortable embracing their inner selves, merging the inner with the outer self, and speaking to colleagues as people, not just as teachers—something I feel comfortable doing, with you, my professor and mentor.

I grew up privileged, in a traditional, ‘blue-collar,’ middle class home—one full of love, opportunity, and guidance, but also rules, discipline and high expectations. My parents married young (sixteen and seventeen) and recently celebrated their forty-second wedding anniversary. They did not graduate from high-school, but they worked hard and did well for themselves. At fifteen years of age, my dad went to work at Dunkley Lumber; he worked his way up to a prominent position and retired at the age of sixty, after forty-five years of committed service. My mom was a ‘stay-at-home mom’ and put everything into raising my brother and I: taking us to school and sports, making healthy meals, and ensuring the house ran smoothly and efficiently.

I was afforded the chance to participate and compete in figure skating, volleyball, basketball, and baseball. Sports instilled me with dedication and grit, as well as a competitive spirit and an appreciation for team and comradery. I started my first part-time job at twelve years of age, working in a busy salon assisting 12 stylists. I walked from school to the salon three days a week, working until nine in the evening, as well as Saturdays and summer holidays. At sixteen years of age, I started working summer holidays at Dunkley Lumber, resuming my salon schedule during the school year. Sports and work were important aspects of my life, but education was imperative. My parents recognized the worth of education in our changing world, knowing the opportunities they had were no longer available without higher education.

I was urged to put great effort into my studies and my hard work was met with positive reinforcement and recognition. I received Principal’s Roll throughout elementary and high-school, graduated valedictorian of my class, and won scholarships to a number of universities, including the University of Northern British Columbia where I attended and received further yearly scholarships and the distinguished Golden Key award. I was dedicated and did very well, but I recognize my privileged circumstances. Nothing had impeded my learning: I had extremely supportive parents who instilled me with the successful learner traits of compassion, creativity, enthusiasm, confidence, risk-taking, strategy, industriousness, and thoughtfulness (Successful Learners); my home was safe, secure, and nurturing; I had a community of friends, family, and coaches; and my educators were “masters” in the field of education.

My path began to shift after my third year of university. I married and did not to return for my fourth year. My husband was from a traditional European family and it was implied that I should be home with him, not attending university in a different city. I began working at Dunkley Lumber, where I functioned in administration for seven years before the birth of my three children. After I became a mother, I was fortunate to stay home and raise my children just as I had been raised. Then, when my sons were five and my daughter two, life was turned upside down—an old growth fir tree fell and crushed the cab of my husband’s truck, leaving him in the hospital with a severe frontal lobe brain injury. His personality and our relationship changed dramatically. We divorced but I was fortunate to have the support of my parents and the instilled traits they, and my upbringing, had afforded me. I returned to UNBC, finished my Bachelor of Arts Degree, and was recognized as the Most Outstanding Geography Student.

After graduation, I immediately started working as an uncertified teacher teaching on call (TTOC) within School District #28. Once in the classroom, it did not take me long to see the correlation between what life had dealt me (the good and the bad) and my emerging teaching philosophy—one based on structure, guidance, ethics, expectations, dedication, and opportunity, as well as the 5 C’s: commitment, care, courage, consciousness, and centeredness (Litz, 2021).

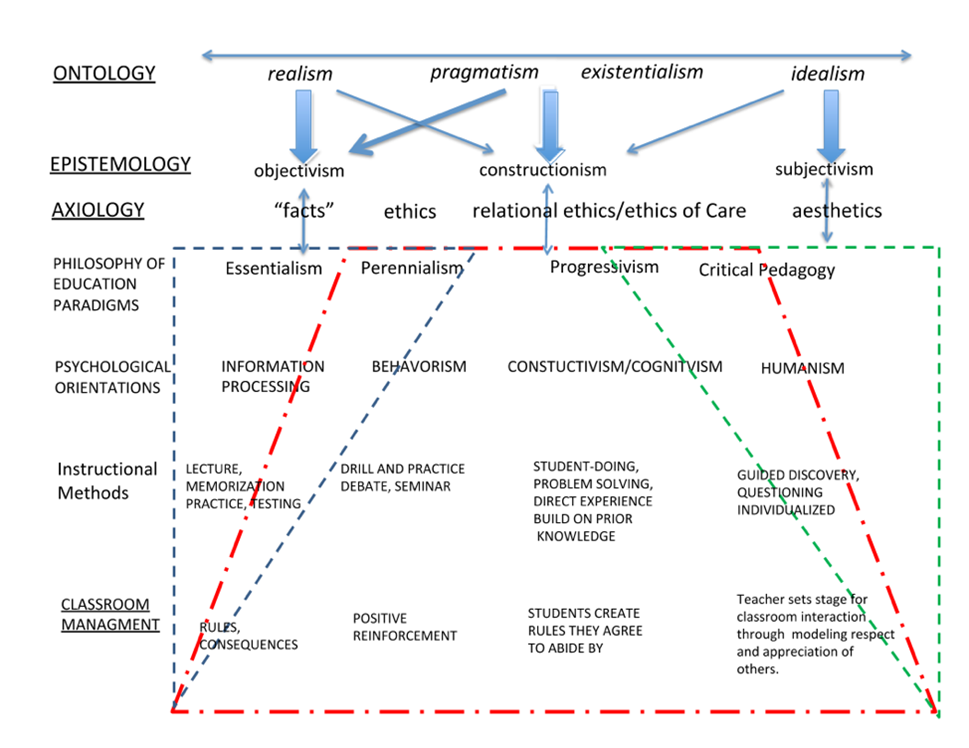

Had you asked me what my teaching philosophy was six weeks ago, I would have told you that it was ‘a little old school.’ But I have been enlightened—by you, other professors, and the scholarly knowledge provided—to a point where I can elaborate on my ‘old school’ ways. Table 1: Philosophies of Education Matrix (below), and the Visual Literacy Activity that accompanied it, from Chapter 5.1: Foundations of Educational Philosophy (SUNY Oneonta Education Department), helped me discern my emerging teaching philosophy:

Table 1: Philosophies of Education Matrix

First, the Visual Literacy Activity had me choose one instructional activity from Table 1 that I felt was an effective means of instruction and explain why. I chose ‘student doing, problem solving, direct experience, build on prior knowledge’ because only by doing can a student better understand concepts and content; only through problem solving and direct experience can students gain familiarity with subject matter/material and understand their own ways of learning; and only prior knowledge can serve as the base upon which students build on their learning.

Second, the activity directed me to choose a classroom management technique from Table 1 that I felt was effective and explain why. I identified ‘positive reinforcement’ because students are more likely to respond positively when given positive feedback; it is a necessary component of engagement and facilitates positive relationships between teachers and student and between student and school expectations/rules/boundaries. In Every Kid Needs a Champion (2013), Rita Pierson, educator with forty years of experience, argues that “kids don’t learn from people they don’t like”; that learning only occurs when there is a positive relationship between student and teacher; that relationships must be built upon positive, not negative, reinforcement—that is: “say they are good or successful enough times and they’ll believe it!”

Finally, the activity had me decipher whether or not my two choices aligned by situating them in Table 1. Instantly, I could see that my choices fell within the central area of the triangle: between the ontologies of Pragmatism and Existentialism; beneath the epistemology of Constructionism; and under the axiology of Relational Ethics/Ethics of Care. My philosophy of education, therefore, is one of Progressivism with a psychological orientation of Constructivism/Cognitivism—this definitely sounds more professional than ‘a bit old school.’ I look forward to building upon my emerging teaching philosophy. This is one of the areas within the Education Program that I am most excited about!

References

Litz, David. (2021, September 16). Qualities of Good Teachers: 5 C’s in Education: The Heart of a Teacher and Metaphors. [PowerPoint]. Retrieved from https://learn.unbc.ca/bbcswebdav/pid-241421-dt-content-rid-2071036_1/xid-2071036_1

Palmer, P.J. (1997). The Heart of a Teacher: Identity and Integrity in Teaching. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 29(6), 14-21.

Pierson, Rita. (2013, May 3). TED Talks Education. Every Kid Needs a Champion. [Video] You Tube – TED. Uploaded on September 20, 2021 from https://www.ted.com/talks/rita_pierson_every_kid_needs_a_champion

Robinson, Ken. (2010, October 14). RSA ANIMATE. Changing Education Paradigms. [Video] YouTube. Uploaded on September 14, 2021 from https://youtu.be/zDZFcDGpL4U

Successful Learners. (2015-2021). Traits. Accessed on October 9, 2021 from

SUNY Oneonta Education Department. (n.d.). Foundations of Education: 5.1 Foundations of Education Philosophy. Attribution Foundations of Education. Uploaded on September 13, 2021 from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-oneonta-education106/chapter/5-1-foundations-of-educational-philosophy/

EDUC 446 Provocation Post #1

Reflecting on the trauma of Residential Schools

Provocation: Residential school classrooms, in a ‘systematic and rigid fashion’, broke the family ties of Indigenous peoples and eliminating their culture and language. They were an instrument of shame and discounted the life experiences of the Indigenous children. Ultimately, these classrooms were places of genocide.

Residential schools violated indigenous children, their families, and entire communities. In this week’s reading, “From Home to School”, out of Celia Haig-Brown’s Resistance and Renewal – Surviving the Indian Residential School (2002), one clearly sees that residential schools were a tool of the colonial government and the Church, set up to eradicate Indigenous culture by removing and alienating its most important gift: its children. For indigenous children, residential school classrooms were not intended to be safe places to learn and grow. Rather, they were intended to systematically strip Indigenous children of their language, values, and beliefs; their ways of being, learning, and knowing.

The many relationships and responsibilities that indigenous children had, within their homes and communities, were not valued or respected in these schools as they did not align with Eurocentric norms, values, and beliefs. Indigenous children were shown zero respect and there was absolutely no space in the educational framework for reciprocity, relevance, reverence, or reflexivity, only blind obedience to European ways and harsh discipline for those who did not obey and/or strayed. Indigenous children had brought with them many important capabilities and capacities (life/survival skills, independence, relationality to family and the land, patience, giving, spirituality), but these were not valued at school or in the classroom because they were not the same values of the European, colonial society.

What a different history there could have been had residential schools not been founded on the principles of European superiority and Indigenous inferiority, but rather on the Nine R’s offered to us by today’s Indigenous scholars: respect, relationships, responsibilities, reciprocity, relevance, reverence, reclamation, reconciliation, or reflexivity. In deep contrast to residential school classrooms, these classrooms include ALL children and treat them equitably. Diversity is embraced and ALL children, regardless of race or ethnicity, share a culturally safe space and are given a voice, feel valued, and are respected. Relationships are essential among students, teachers, caregivers, and the wider community; all are valued stakeholders in building capacity and contributing to learning.

Students are responsible for their learning and are given the space to learn and make mistakes, knowing they have the support and guidance of teachers and fellow learners. These classrooms are reciprocal, there is always a two-way street of teaching and learning and what happens within their walls is relevant—historically, culturally and spatially. Reverence is given to the land and, individually and collectively, the classroom works towards reclamation and reconciliation—recognizing the truth, acknowledging that what was done in the past was wrong, why it was wrong, and then focusing on what needs to be done to heal and mend those wrongs.

In these classrooms, reflexivity is taught and practiced. Students are aware of difference, but rather than condemn it, they celebrate and respect it. Students, teachers, and all stakeholders learn from, and teach, one another. This is what we, as future teachers, must embrace in order to transform our classrooms into places of Truth and Reconciliation; into places that assist the healing of generational trauma, which continues to weave through the fabric of indigenous children as a direct result of residential schools.

EDUC 393 Cross-curricular Reflexive Writing #1

Phew, where do I begin?!?! My brain has been buzzing with so many different thoughts, queries, and questions during these initial few weeks! Actually, if I am being reflexive, reflective, and completely honest, it has been buzzing around thoughts, queries, and questions pertaining to teaching and education for the past few years! Coming to the University of British Columbia’s School of Education after two years of experience as an uncertified teacher teaching on call (TTOC), I feel ready to embark on this journey of knowledge, experiential learning, and growth, but I also have many concerns about the role of the teacher and the context of teaching in our rapidly changing world.

I am not implying that teachers, and the teaching profession before me, did not experience change. However, in the most recent era of expanded globalization, unparalleled technological advancement, the explosion of knowledge, and the blowup of social/digital media, how we teach, what we teach, why we teach, where we teach, and how our students learn and cope with the how, what, why, and the where of our teaching, has changed dramatically. Teachers are expected to adapt at an ever-increasing rate of speed in order to keep apace. My concern, in line with Sir Ken Robinson’s (2010) concerns, lies in our ability as teachers to keep up to such changes when the education paradigms put in place around us are not adapting.

Robinson (2010) argues that we are failing our students because the current education paradigm is trying to meet the future needs of educating children by doing what we did in the past. As such, it is alienating millions of kids who do not see the point of going to school. This is a very sad reality, which I have seen play out in the classrooms I have taught, especially in the intermediate, junior, and high school grades. Robinson calls for a complete shift, a total revamp, of the educational paradigm—one that moves away from conformity and standardization and toward creativity, divergent thinking, and collaboration. According to Robinson, this paradigm shift must rethink human capacity and change the structures and habits of our educational institutions and the habitats they occupy. Robinson posits some very important questions that I think can guide our future work as teachers. The first, economic, asking us to question how we educate our children to take their places in the economies of the twenty-first century when we cannot anticipate what the economy will look like in this always changing, advancing world. The second, cultural, asking us to question how we educate children to help them better understand and value their cultural identity while we are in the turmoil of globalization.

Did I think about these issues, concerns and daunting questions when I was in my youth? Thank goodness, no!! Was it because public education in my youth, and my teachers within it, were without flaws? Again, no. Yet, when I was a student, I do not remember seeing the extent of challenges in public education, in my school buildings, or in my classrooms, that I see today. Part of this, no doubt, has to do with my lens. As a student, I was looking through the lens of child. As a teacher, I am looking through the lens of an educator, concerned with meeting the needs of her diverse students. As a mother, I am looking through the lens of a parent, concerned for her children’s education. Still, lenses aside, I am willing to bet that if I could send a classroom of today’s students back in time 25 years, so that they were sitting in one of my elementary or secondary classrooms, they would agree that challenges have grown significantly.

The question becomes: is all hope lost? Ben Johnson (2009), argues that, although it is complicated, there are “beacons of hope”—beacons that understand that it is not what is learned, but how it is learned; beacons that understand that a teacher is no longer a “purveyor of knowledge” but a “learning leader”; that the classroom and it’s learners should not be compartmentalized, but rather be “transformed into a high-performance learning team” (p. 2). Johnson argues, “long past are the days where teachers could be effective by themselves”; adding that, “[t]he survival of public education will ultimately be determined by the extent to which teachers embrace peer collaboration in planning and implementing high-performance learning teams”; and finally, that “teachers must honor and value the time that students spend in our classrooms by devoting the majority of it to the only real teaching that has a chance of keeping up with the ever expanding volume of knowledge” (p. 3). As teachers, we need to give students the tools they need to be successful, we need to help them understand the processes of learning, and we need to give them a solid foundation in the essentials of literacy, numeracy, and both community and digital citizenry.

Given that I am here today, as a Teacher Candidate with the goal of teaching as a certified teacher in my hometown community of Quesnel, on the traditional and unceded territory of the Lhatko Dene First Nation, shows my hope is not lost! I have faith in teachers, the teaching profession, and public education. I believe that educational paradigms can shift and I am confident that the Bachelor of Education program will prepare me for being a part of that shift. I endeavor to take any and all challenges of teaching in stride. I want to support students and ensure that public education and my teaching is accessible, that it is relevant, and that it adapts to keep pace with our ever-changing world. The moment I stop believing that it, and I, can be these things or, more importantly, when our students stop believing it, is the moment we—as a society—will find ourselves in trouble. The day our education system fails our youth is the day we fail as a society! It is up to us, as teachers in the teaching profession, to ensure this does not happen.

References

Johnson, Ben. (2009, November 19). Why Do We Teach? edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/teacher-role-redefined

Robinson, Ken. (2010, October 14). RSA ANIMATE. Changing Education Paradigms. [Video] YouTube. Uploaded on September 14, 2021 from https://youtu.be/zDZFcDGpL4U

Over the past two years, I have had the pleasure of working as a non-certified teacher teaching on call (TTOC) within School District #28, Quesnel. I have been called to dozens of classrooms, from kindergarten to grade 12, and have had the opportunity to teach a variety of learners and subjects. It has been a wonderful experience and I have learned and grown so much—and heard many metaphors! When the subject of metaphors and teaching was addressed in our first EDUC 394 lecture, I was super enthused and excited to discuss and share my personal metaphor of choice. But before I get to that, I want to touch upon a few metaphors that I have heard echo off school and administration walls over the past few years. These metaphors have, in their own right and at certain moments in time, rang true in my journey and have contributed to, and shaped the metaphor I feel close to my heart today—that of teacher as astronomer/astronaut.

I encountered my first metaphors while being interviewed for my current TTOC position. I had no official classroom experience on my resume, but I did have volunteer coaching listed and so my interviewer reassured me that being a teacher was like being a coach. Teachers, like coaches, support and encourage their students; they cheer them on and lift them up when they feel down. Teachers, like coaches, are knowledgeable and skilled in what they do and it is their love of knowledge and skills that motivates them to pass it on to the youth they work with. Teachers, like coaches, come up with practice and game plans, but ultimately a teacher needs her students, like a coach needs her players, to show up, participate, engage and want to learn—and thus it is up to coaches and teachers to ensure that the learning environment is accessible to all, engaging, enjoyable, and fun.

My interviewer also noticed the six-year gap on my resume, a hiatus from the workforce where I had been raising my three young children on a full-time basis. A conversation of motherhood ensued and I was assured that my unpaid work in the home would not go unnoticed in the classroom as teaching was, essentially, a caring profession—that is, teachers are caregivers. Teachers, like parents and guardians, are responsible for those in their care. It is the job of the teacher and caregiver to ensure that, first and foremost, children’s needs are met and of utmost importance; that children feel safe (emotionally, physically, mentally, spiritually); that they are protected, nurtured, respected, and given every opportunity to become fully engaged and active citizens of their communities. Teachers, like caregivers, help children see and realize their own potential while understanding that it is not their perceived needs for the child that matters, but the actual needs of the child.

After much reassuring talk, the interviewer moved to tougher questions, asking how I handled stressful and unpredictable situations, as “teaching is often tough and being a teacher is not always smooth sailing.” Teacher as sailor, like discussed in class, has many parallels. The sea is rough and unpredictable, as are classrooms, and thus sailor and teacher must be prepared for anything. Exploring unchartered waters and getting off-course are facts of life for a sailor, as they are for a teacher, so both have to be skilled and resourceful. A sailor cannot predict the weather, just as a teacher cannot always predict the climate of her classroom or how students will engage, adapt, behave, and so forth. My interviewer continued, saying that the challenges of being a classroom teacher would be compounded for me, given the fact that I was uncertified and lacked the teacher-training gained in a School of Education program.

Yet, at the end of the interview, I was hired on the premise that I would do all I could to fill my toolkit (teacher as carpenter, mechanic, and sculptor all came to mind). I immediately set about garnering the skills and gathering the resources I needed to be successful in the classroom: attending professional development days and sessions with guest speakers; shadowing teachers with a wealth of expertise; sitting in the basement of the District Administration Office, scouring teaching and learning resources for days; and collaborating with as many teacher-colleagues as I could, trying my best to absorb information like a thirsty sponge.

Despite my efforts, there were moments (sometimes entire workdays) in those first few months where I felt as though I had been “thrown into the deep end”, where I questioned my ability to stay afloat. Thankfully, I did not drown, but it was not my swimming skills alone that got me through. I had a sturdy raft, in the form of amazing teacher-colleagues, that came to my rescue when I needed support. It was here where I started to see another metaphor emerging—that of teacher as lifeboat. I had been on the receiving end of the lifeboat as a new teacher learning from teachers, and eventually I started experiencing instances where I was the lifeboat for my students. Helping them stay afloat during their days at school, ensuring they had the resources and support they needed to be successful in the classroom.

As the months went by, and the months turned into years, I slowly I started to develop a metaphor of my own—that of teacher as astronomer/astronaut:

Astronomers are scientists who study the universe, its objects and how it works. They aim to push the boundaries of human knowledge about how the universe works by observation and theoretical modelling. Astronomers rarely work in isolation, and in addition to being aware of what colleagues at your institution do, astronomers are expected to keep up with the published literature from around the world and to be able to put their research work into the context of other research (Prospects).

For astronomers, the focus is the universe, its objects and how it works. For teachers the focus is the classroom (which often seems as broad as the universe), its objects (children, like the stars and planets, numerous, varied, and unique), and how they work (individually and collectively). Like astronomers, teachers push the boundaries of knowledge about how things work by both observation and theoretical modelling. Teachers, like astronomers, rarely work in isolation as they collaborate with colleagues in their schools, districts, provinces, countries, and global professional community. Teachers, like astronomers, are expected to keep up to date on evidence-based research in their field. In addition to research, teachers and astronomers both embark on guided exploration: astronauts exploring space and its objects; teachers exploring classrooms and the students within them.

Astronomers look to the stars and planets to guide them, while teachers look to their students—their stars—to guide them and their work. Every student, like every star in the night sky, gives off their own light within the classroom. Some students shine brighter on different days and at different times, but each one has light within them. Each student, like each star, is unique—no two the same:

The best tool we have for studying a star’s light is the star’s spectrum. A spectrum (the plural is “spectra”) of a star is like the star’s fingerprint. Just like each person has unique fingerprints, each star has a unique spectrum. Spectra can be used to tell two stars apart, but spectra can also show what two stars have in common. […] Stars do not give off the same amount of light at every wavelength. […] A typical spectrum for a star has a lot of peaks and valleys (Sky Server).

Throughout a teacher’s life, she will come in contact with many unique fingerprints and a spectrum of differences. She will see the peaks and the valleys and meet each student where they are, knowing that as some stars shoot, others will fall. But, no matter what, she must continue to focus on the stars in front of her—for these stars are shining and they continue to give her hope and purpose.

Therefore, while I have used other metaphors—teacher as zookeeper or cat herder (usually referenced playfully when teaching in kindergarten or grade 1); teacher as referee or fireman (after a day spent mediating squabbles between students or putting out “fires”); and teacher as compass (when I have had the opportunity to guide children in their educational journeys)—I hold the metaphors I have detailed above closest to my heart. These metaphors touch upon who I am as a person and, as Parker Palmer (1997) eloquently details, teachers teach who they are!!

References

Palmer, P.J. (1997). The Heart of a Teacher: Identity and Integrity in Teaching. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 29(6), 14-21.

Prospects. Job Profile: Astronomer. Retrieved from https://www.prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/astronomer on September 18, 2021.

Sky Server by Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Types of Stars. Retrieved fromhttp://skyserver.sdss.org/dr1/en/proj/basic/spectraltypes/ on September 18, 2021.